My printing technique is intricate, leading to lengthy captions during exhibitions. "Woodcut rubbing print, pigment print, Urauchi, waxing, and pastel and mica drawing". If I were to detail the materials used in my printing arts, they would become even more extensive.

In particular, the woodcut rubbing prints I utilize function as both recording and transmitting media. The inherent eroticism of this technique plays a pivotal role in each of my works.

Recently, rubbings, known as ‘takuhon’ in Japanese, have been frequently introduced as a technique in Mokuhanga or woodblock printing. However, rubbing is the world’s oldest method of recording and transmitting information, involving the meticulous transfer of characters engraved on bronze or stone monuments.

The origin of rubbings is believed to date back to around the 17th century BC to 1046 BC in ancient China, when emperors engraved their words onto bronze or stone monuments. To promote the emperor’s authority, rubbings of these authentic stone monuments were made and distributed worldwide. There is no doubt that people from that era profoundly reverential medium the rubbings.

On the other hand, Mokuhanga, to this day, includes the element of printing. Its origin can be traced back to the ‘One Million Pagoda Dharani Sutra’ created during Japan’s Nara period in the mid-eighth century. This is considered the world’s oldest surviving print produced by woodblock printing.

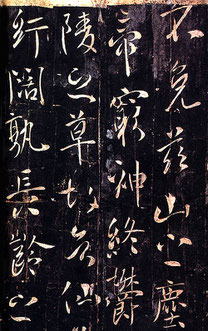

拓本[唐太宗]李世民 《温泉铭》(部分)

Rubbing "Hot Spring Inscription" written in running script by Li Shimin, Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (Partial)

This image is in the public domain.

While rubbings and woodcuts both share the characteristic of producing multiple prints, it’s not widely known that their purposes are entirely different. It’s said that Jakuchu, a Japanese artist from 1716-1800, had a preference for woodcut rubbing prints. He may have been drawn to the unique aspects of this medium, as well as the fascinating process of printing.

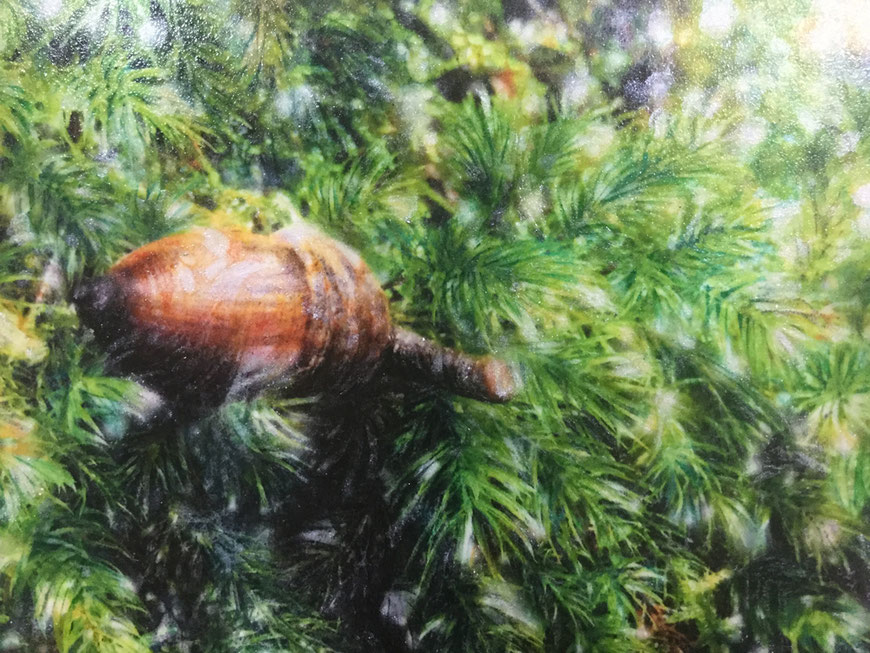

I understand that woodcut rubbing prints have an exceptionally delicate expression that can only be achieved through this technique. I also consider the historical context of this technique to be very important in my work, especially because I work with photography. I handle materials that present various challenges, I know when I display them like museum pieces, they can serve as mediums for recording and transmitting information.

However, I believe that if that’s all there is to it, something is missing. What is it? It’s a memory. Memory is a reconstruction and creation of the world that we have seen and felt. The ability to express this in some form is the essence of creation. I use many complex techniques, like those mentioned above, to revive memories of the places I’ve visited and the things I’ve collected. And I need the woodblock that I have engraved. For me, the act of carving woodblocks carries an eroticism, as if the act and the emotion itself are being etched directly onto the woodblock. The rubbings I print as if to trace that feeling/sense are so vivid that I feel the very essence of life.

私が版画で使う技法は複雑なので、キャプションはいつもやたらと長い。『木版拓摺り、インクジェットプリント、裏打ち、蝋引き、パステルと雲母による手描き』。さらに作品に使った素材を記載すれば、もっと長くなる。私が主に使っている木版拓摺りという技法は、情報記録伝達メディアという側面と、圧倒的なエロティシズムがあり、私の各作品において極めて重要な役割を果たしている。

近年、木版の拓本が木版拓摺りという木版画の技法として紹介されることが多くなったが、拓本は青銅や石碑に刻まれた文字を丁寧に写しとる世界最古の情報記録伝達メディアである。拓本の起源は古代中国の紀元前17世紀〜紀元前1046年とされ、皇帝の言葉を青銅や石碑に彫り、彼らの権威を広める為に「本物の石碑」を写しとり、それを世に広めた。当時の人たちにとって拓本はたいそう畏れ多い媒体だったに違いない。その一方で、木版画は現在に至るまで印刷としての要素を含んでおり、その起源は、8世紀半ばの奈良時代に完成した『百万塔陀羅尼経』に遡る。これは、木版によって制作された現存する世界最古の印刷物と言われる。

百万塔陀羅尼経 One Million Pagoda Dharani Sutra

出典:ColBase(https://colbase.nich.go.jp/)

実は拓本と木版印刷は版画の特性である複数性を持つが、その目的は全く違うものであったということは、あまり知られていない。若冲も木版の拓本を好んだと聞くが、その摺りの過程の面白さだけでなく、このような違いに惹かれたのかもしれない。

私は木版の拓本でしか得られない非常に繊細な表現だけでなく、このような歴史的背景を持つこの技法が、私の仕事の中ではとても重要であると考えている。なぜなら私は写真を扱うからだ。また色々と事情を抱えた素材を扱うこともあるが、それらを博物館のように展示すれば、情報の記録と伝達の媒体になる。

しかし、それだけだと圧倒的に何かが欠ける。それは何か。記憶である。記憶は自分の見て感じた世界の再構築であり、創造である。これを何らかの形で生み出すことが表現だ。私は自分が行った場所や集めた物の記録を記憶する為に、冒頭のような多くの技法を複雑に使うが、必ず木版が必要となる。私にとって、版木を彫るという行為は、あたかもその行為と感情そのものが直接版木へ刻まれているかのようなエロティシズムをもたらす。

そして、その感覚をなぞるように摺る拓本は、生命の本質を感じるほどに鮮やかだ。

古典から現代: テクニックの融合

From classic to modern: A Fusion of Techniques

My artistic process involves a harmonious blend of classical, traditional, and modern techniques. Here’s a breakdown of how I create my artwork:

1. Photography and Filming:

I start by capturing a wealth of visuals through digital cameras and smartphones by my eye. These images serve as the foundation for my artwork.

2. Digital Editing:

After selecting the most compelling photographs, I edit them on my computer. This step allows me to enhance and refine the visual elements.

3. Printing on “AWAGAMI” Japanese Paper:

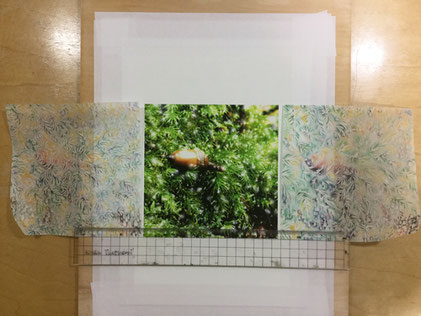

Finished with the digital edits, I printed the image on “AWAGAMI” Japanese paper for pigment print. The choice of paper is crucial for achieving the desired texture and color depth.

4. Rubbing and Woodblock Carving:

I carve woodblocks by hand, introducing intricate touch, I print to use rubbing on Ganpi paper, introducing exceptionally delicate expression colors.

5. Layering Techniques:

To add depth and complexity, I employ a Japanese technique called “URAUCHI.” I paste two sheets of Ganpi paper onto the AWAGAMI print, creating a composite structure.

6. Wax Infiltration:

After drying, I infiltrate the artwork with wax. This process renders the paper translucent, lending an ethereal quality to the piece.

7. Pastels and Mica:

Using pastels and mica, I accentuate specific areas. Mica, inspired by Ukiyoe Hanga and Kyoto Karakami paper, helps me convey the light.

8. Multilayered Composition:

What may appear as a single sheet of paper is, in fact, a composite of multiple layers. Each technique contributes to the overall effect, bridging the gap between classical and contemporary art. In this fusion of methods, I believe we glimpse the future of artistic expression—a harmonious coexistence of tradition and innovation.

私のプロセスには、古典的、伝統的、そして現代的な技術が調和している。

1. 写真撮影と撮影:

まずはデジタルカメラやスマートフォンを通して豊富なビジュアルを目で捉える。これらのイメージは私の作品の基礎として機能する。

2. デジタル編集:

最も魅力的な写真を選択した後、コンピューター上で編集を行う。 このステップにより、視覚要素を強化し、洗練することができる。

3. 阿波紙への印刷:

デジタル編集を終えた画像を顔料系インクジェットプリント用の阿波紙にプリントする。紙の選択は、望ましい質感と色の濃さを実現するために重要だ。

4. 拓本と木版彫刻:

緻密なタッチで木版を手彫りし、雁皮紙に拓摺りすることで非常に繊細な色彩表現が得られる。

5. レイヤリングテクニック:

深みと複雑さを加えるために、裏打ちをする。 インクジェットプリントされた阿波紙の上に雁皮紙を2枚貼り付けて複合構造を作る。

6. 蝋の浸透:

乾燥後、蝋を作品に浸透させる。このプロセスにより紙が半透明になり、作品に幻想的な質感が与えらる。

7. パステルと雲母:

パステルと雲母を使用して、特定の領域を強調します。 浮世絵版画と京唐紙からインスピレーションを得た雲母が、光を伝えるのに役立つ。

8. 多層構成:

一枚の紙のように見える作品は、実際には複数の層の複合体である。 それぞれのテクニックが全体的な効果に貢献し、古典芸術と現代美術の間の橋渡しをする。これらの手法の融合には、伝統と革新が調和して共存する芸術表現の未来が垣間見えると私は考える。